As teachers we plan ahead. The rhythms and cycles of school life are the template over which we lay our own lives, and I think this is why the current hiatus has hit many of us hard. Like a bereavement, that which we have built our life around has suddenly disappeared.

So what do we do? Of course, we revert to type and start planning ahead, considering what we might face when students return to “normality”. Regardless of when that might happen, the principal concern among many teachers is, of course, that the gap has widened.

But what gap? Between whom? And how do we close it? I share a few thoughts in this blog.

Falling Back

Those hardest to reach in school will have done even less at home, and those hardest working may have done even more work, but it’s unlikely that they would have learned any more at home than they would have with a teacher present. They haven’t necessarily gained. But we will have a gap in work done, and ultimately a gap in learning between these two extremes. It’s vital that we properly diagnose these gaps in the entire student body, and then begin to teach them properly from a developmentally appropriate point?

Assessment

Thoughtful assessment, and the flexibility of both our curriculum and our teachers will play an important part here. We’ll probably need to design these assessments ourselves for two reasons;

-

- to allow for the lockdown learning to be given proper attention based on our context, and

- because it must feed in to what we do next

The assessment and the next curriculum steps need to be planned together. Fortunately we’ll probably have months to get it right. There’s even time for a training course.

Curriculum

Remember all that work and thinking you did on the curriculum? You might end up putting aside the work for a while, but keeping the thinking. What would you expect students to know on their return? How will you support those who haven’t worked at home (they’re children – it’s not their fault) whilst making sure those who worked hard are rewarded and extended? Importantly, how will you get everyone (students and teachers) to buy in to your plans?

Teachers

Are you planning the timetable, or appraisals for next year? Keeping teachers in their comfort zone for the year is no bad thing – they’ll have enough other stuff to deal with that is more important.

Motivation to Improve

And when the children return, we will also need to be mindful of a gap in attitude, and please indulge me for why. Before I was a teacher I worked as a consultant for a software company. Businesses would pay up to £1000 a day for my visits (I know! And this was the 90s!) and so the stakes were high. But being young and slack, I admit, I sometimes saw a technical fault or a lack of preparation on their part as a positive. What luck! Those expectations were now diminished, and I didn’t have to perform at my best because other factors were at play which weren’t my fault.

So, imagine a typical student in Year 10. Like me, out for an easy life. Why should he bother now? It’s not fair, it wasn’t his fault. Can’t they just give him his FFT grade like they did last year? For me, this issue will be critical in September and we’ll end up fighting too many fires unless we plan carefully for it now. Caroline Spalding described some excellent sociological strategies for getting everyone pulling in the same direction and feeling part of something bigger in her #REdDurringtonLoom presentation here.

Forging Ahead

Mark McCourt has said that this will be the most important school year in generations. This means that as a profession and in our own schools we need to plan wherever we can for their return, from the known-knowns right through to the unknown-unknowns.

Much has been said of the extra things we could do to make up for the lost time. Interventions, priority opening, extra lessons, devices, extra homework. This is where I think we are only tinkering at the edges – students still only have a finite amount of time in their lives, and we need to be ever more mindful of the penalty paradox and the welfare of our staff.

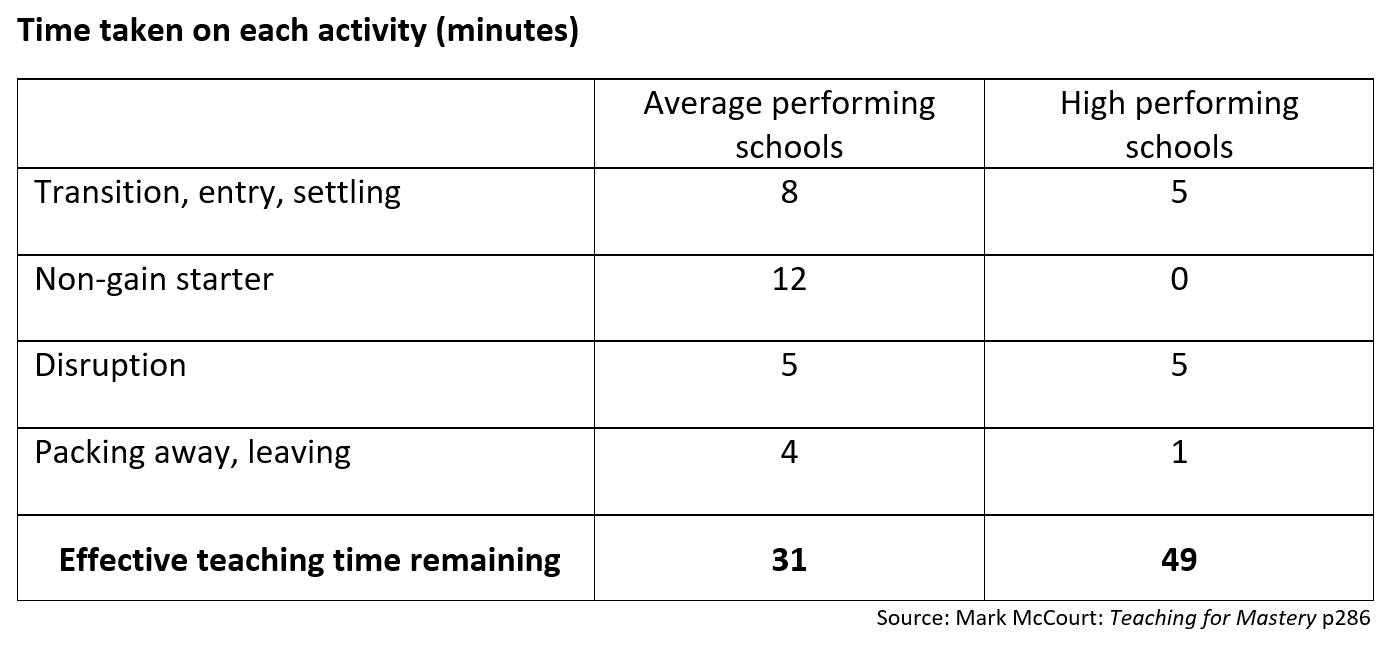

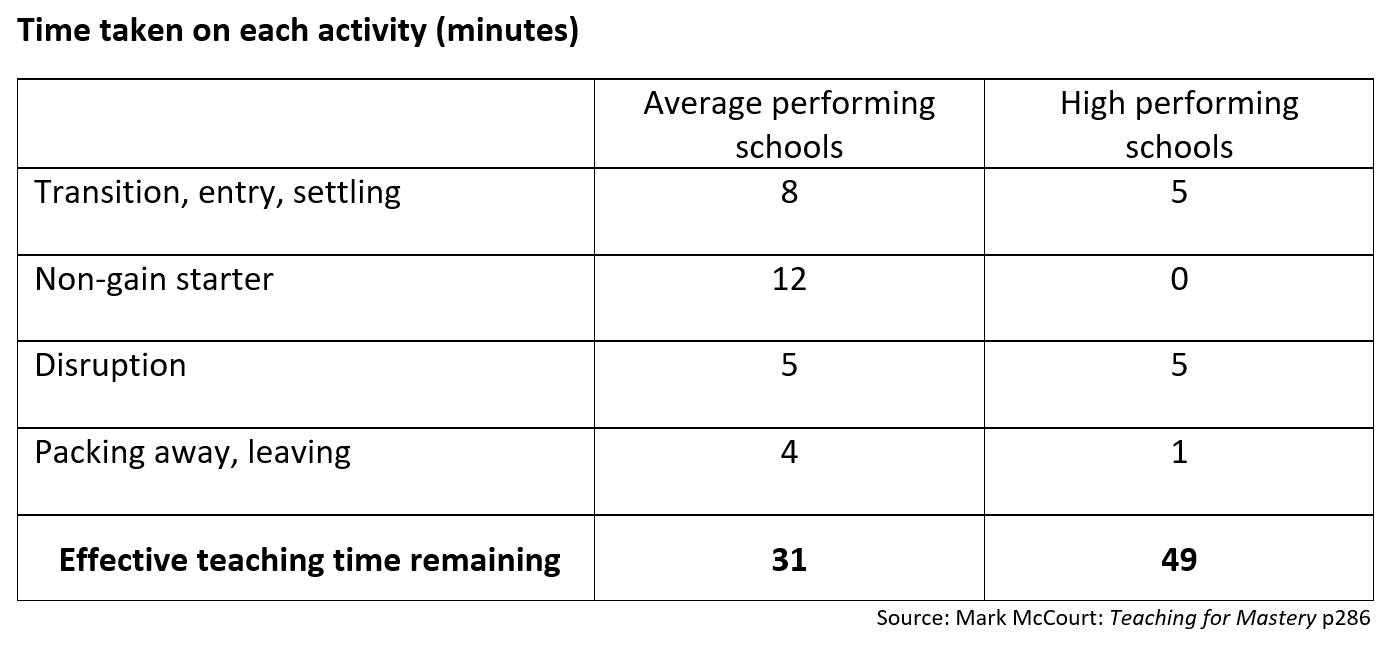

My view is that our greatest gains can still be made in lessons. Every minute counts. While things may have improved in some schools since this study from 2010, an analysis of the effective use lesson time in the average school is shocking:

I know what you’re thinking, so let me explain. Here, a “non-gain starter” is defined as any starter that is not part of the continuation of this learning episode. It’s common (and probably effective) for a lesson to begin with a retrieval activity not linked to the lesson’s main purpose. This would be classed as a “non-gain” starter, but I would not argue with anyone who claimed that this was an effective use of lesson time.

However. Is it? Really? Are you sure? If you can answer “yes” to all these questions then I’ll believe you.

- Do students always arrive on time and set straight to work?

- Do students see the starter as compulsory?

- Is there always a consequence to not finishing the starter?

Conversations with the students in this study revealed that they saw the starter as “optional”, and that there was no consequence to missing it because it ‘wasn’t the real lesson’. Punctuality was poorer in lessons with a “non-gain” starter. For the record, we use “non-gain starters” in my department and I certainly can’t answer yes to these questions! Just before schools closed, I was tackling a year 8 girl who was late and had not set to work. Her words; “but it’s only the starter!” cut right to my heart.

Let’s assume for the moment that you’re feeling all smug because you answered “yes” to all of the questions above. Well done.

What about the other six minutes?

No school leader will tell you they have behaviour in lessons completely sorted. But every school leader would seize the offer of an additional 20% curriculum time, for free.

To gain those extra six minutes, or more, many attitudes need to change. But haven’t they already? Won’t they? In my view this is a whole school issue that leaders could be planning for right now. We have a huge opportunity ahead of us, a chance to help students to truly believe they’re all in it together, their future is in their hands and actually, their response to this situation is theirs to define.

The restart will present a huge challenge. Yes, it’s about assessment. Yes, it’s about curriculum. But mostly it’s about winning the hearts and minds of some traumatised and anxious children.